Emacs - “Editor MACroS”

Table of Contents

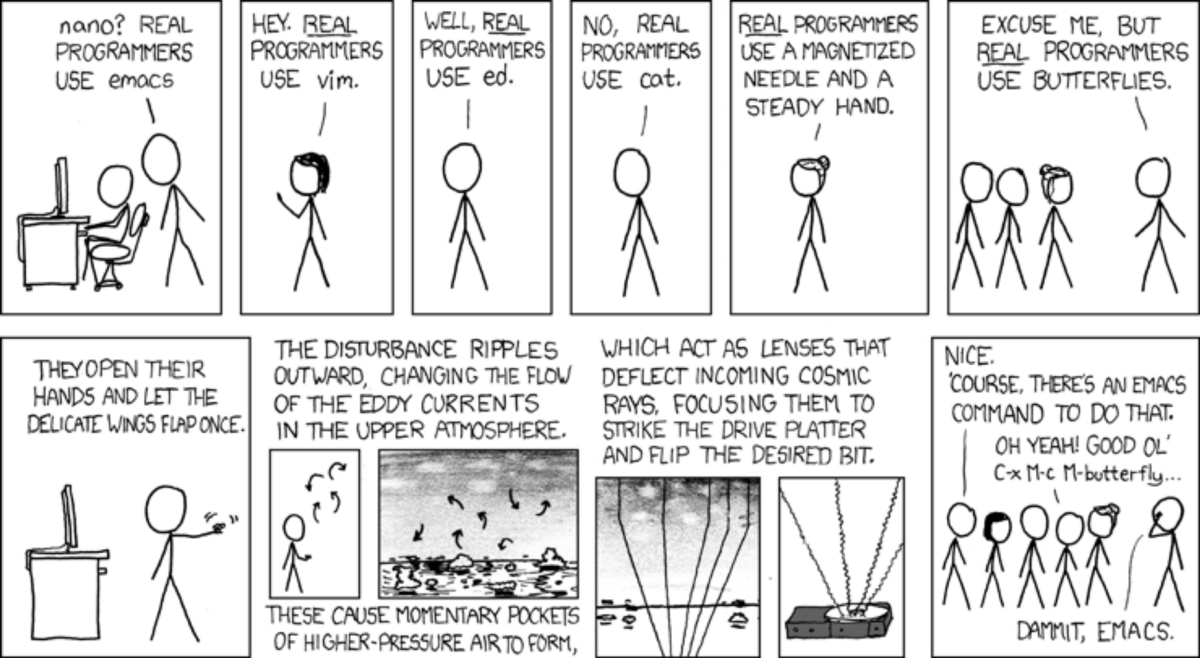

1. XKCD

2. What is Emacs?

3. From GNU.org:

Emacs is “an extensible, customizable, free/libre text editor — and more. At its core is an interpreter for Emacs Lisp, a dialect of the Lisp programming language with extensions to support text editing.”

3.1. Emacs history

3.1.1. From the EmacsWiki:

Emacs began at the Artificial Intelligence Laboratory at MIT. Beginning in 1972, staff hacker CarlMikkelsen added display-editing capability to TECO, the text editor on the AI Lab’s IncompatibleTimeSharingSystem (ITS) “Display-editing” meant that the screen display was updated as the user entered new commands; compare the behavior of “ed”. In 1974, Richard Stallman added macro features to the TECO editor.

In 1976, Stallman wrote the first Emacs (“Editor MACroS”), which organized these macros into a single command set and added facilities for SelfDocumentation and to be extensible.

3.2. Emacs is a super extensible “editor” that is written in Elisp

3.2.1. “Editor”

- Emacs does much more than edit text

To show itself off, Emacs by default comes with a full game of tetris!

(tetris)

- Besides being a great tool to play tetris when you’re bored and your boss is looking away, Emacs can also:

- Write emails with the `mu4e` package

- Write documents with Org Mode (more on this later)

- Be your window manager with the exwm package

- I’ve given this a try, but I’m gonna stick with dwm

Browse the internet with eww!

- Eww in action

(eww "https://gnu.org")

- Besides being a great tool to play tetris when you’re bored and your boss is looking away, Emacs can also:

3.2.2. Emacs Glossary

- Weird key-binding notation?

- “C” is control

- “M” is alt/meta

- “S” is shift

When there is a “-” between two keys that means press them together.

“C-x C-f”: Control and x and then control and f (you can also hold down control)

- What is a “buffer”?

Buffers hold a file’s text. In the example before with Tetris, `(tetris)` creates a Tetris buffer.

You can think of buffers as “tabs” in a browser or GUI text editor

- What is a “window”?

A window hosts a buffer. When you make a split, each side is a “window”

Cycle between windows with “C-x C-o”

Close a window with “C-x 0”

- What is a “frame”?

A frame hosts a complete instance Emacs. They are equivalent to “windows” in a window manager. It’s common to only really ever use one.

- Good-to-know keybindings

- Quit emacs with “C-x C-c”

- Open a file with “C-x C-f”

- Save a file with “C-x C-s”

- Accidentally pressed a different command and you have no idea what you’re looking at? “C-g” will probably get you out of it.

- “C-x u” to undo

- “C-space” to select a region and “C-g” to stop selecting it

- With a region selected, cut it with “C-w” (this is also known as “killing”)

- Paste with “C-y” (this is also known as “yanking”)

- Window/buffer keybindings:

- “C-x C-b” changes the buffer in the current window

- “C-x 2” splits a buffer vertically

- “C-x 3” splits a buffer horizontally

- “C-x o” changes the current window

- “C-x 0” kills the current window

- “C-x k” kills the current buffer

- Movement keys

- “C-n” goes to the next line

- Vim: “j”

- “C-p” goes to the previous line

- Vim: “k”

- “C-f” goes to the next character

- Vim: “l”

- “C-b” goes to the previous character

- Vim: “h”

- “M-f” and “M-b” goes forward/back a word

- Vim: “f” and “b”

- “C-a” goes to beginning of a line

- Vim: “0”

- “C-e” goes to the end of a line

- Vim: “$”

- “C-n” goes to the next line

- Documentation

- “C-h a” to find the keybindings for a command, or to search for a command

- “C-h k” to find the name of a function tied to a keybinding

3.3. First look at Elisp

Elisp is a dialect of Lisp specifically written for Emacs. Everything in Elisp is a function. Drawing the buffer, splitting windows, moving the text cursor, are all functions you can call in Elisp. It makes it super easy to configure Emacs if you know just a little bit of Lisp.

In fact, let’s take a look at Elisp and how we can start to customize our own environment programatically.

3.3.1. Lisp’s simple syntax

In Lisps, the syntax is super simple. Everything is essentially a linked list, both in data and in source code. Lists are written like `(a . (b . (c . NIL)))`. This would be equivalent to the linked list `a -> b -> c -> null` (nil = null = false in lisp).

However, writing a dot and a period becomes cumbersome when you have even a medium sized list. This is where s-expressions are useful.

S-expressions are written with parentheses around them, like so: `(a b c)`. This is shorthand for the above `(a . (b . (c . NIL)))`.

By convention, Lisp code is written with the function as the first element in the linked list, and arguments of the function afterwards.

- Sum of numbers

- Difference of numbers

(- 3 2) ;; 3 - 2

- Printing values

`princ` will take the value of a lisp object at print it:

(princ "Hello, world!")

- Multiplication

(* 3 5) ;; 3 * 5

- Division

(Integer math)

(princ (/ 3 5)) ;; 3 / 5

(Floating-point math)

(princ (/ 3.0 5)) ;; 3 / 5

- Order of operations

(setq a (/ (* 2 3) (- 6 1))) ;; variable a = (2 * 3) / (6 - 1) = 1 (setq b (- (* 2 (/ 3.0 6.0)) 1)) ;; variable b = (2 * (3 / 6)) - 1 = 0 (princ (list a b)) ;; Print a linked list a -> b -> nil

3.3.2. Writing a simple function in Elisp

Here I will split this window into three sections with Elisp:

(split-window-right) (split-window-below)

To cycle forward through these windows, I press “C-x C-o”.

However, what if I want to go back a window?

Emacs doesn’t provide a keybinding for this by default (to my knowledge), so let’s make it in Elisp ourselves!

- Definining a function to go back a window

Functions in Elisp are made with the `defun` macro (macros are for a different presentation) and the syntax is:

`(defun function-name (list-of-args) function-body)`

The last element in the function body is what is returned

For example, to make a function to find the hypotenuse of a right triangle with lengths a,b:

(defun pythagoras (a b) (setq a-squared (* a a)) (setq b-squared (* b b)) (sqrt (+ a-squared b-squared))) (princ (pythagoras 5 12))

Defining the function

(defun go-back-window () (interactive) ;; makes a function an interactively-callable command (e.g. allowing call by a keybinding) (other-window -1)) ;; (other-window n) goes n windows forward in the window stack

(go-back-window)

Let’s add a key binding for this!

(global-set-key (kbd "C-c u") 'go-back-window) ;; We specify the name of the function by turning it into a "symbol"

4. Why is Emacs better than Vim?

4.1. Org mode

4.1.1. “Your life, in plain text”

Every single org file is represented in Plain Text. Similar to markdown, it’s a way to format this plain text so that it’s readable and understandable by humans, but still parsable and extensible for programmers. This presentation itself is in org mode!

4.1.2. Programming in org mode

You may have noticed these things here in my presentations:

(princ "I run in a source block!")

These blocks, called “source blocks”, are blocks of code you can run interactively in an org mode document. It’s incredibly common for emacs users to define their init.el (the file emacs will run first when it starts up) in an org mode document, whose source-blocks are cut out and placed automatically.

They are also great for presentations, and taking notes in a CS class

These blocks are run with “C-c C-c”

4.1.3. Math homework in org mode

Org mode also has amazing LaTeX support. It’s really easy to add mathematical symbols in an org mode document.

- Inline org mode math

- A function f

S = {students at USU} M = {members of FSLC} B = {cool, uncool}

f : S → B ∋ f(x) = { cool (x ∈ M), uncool }

- Definition of a proper subset

Let A,B be sets: A ⊂ B ⇔ ∀ x (x ∈ A ⇒ x ∈ B) ∧ A ≠ B

- Let’s make it pretty!

Right now, it doesn’t look pretty, but watch this:

(org-toggle-pretty-entities)

- A function f

- Exporting to LaTeX

There’s still a lot more flexibility in completely exporting an org mode document to a LaTeX pdf. You can define equations, include diagrams, captions, etc. It’s super simple too! Just use the command `C-c C-e l o` (you need latex packages installed)

4.1.4. Export to literally any format

With the export menu, you can easily export to Open Office documents, HTML pages, Markdown, iCalendar (you can make agendas in Emacs), really anything!

4.2. Amazing package support and community

Yeah yeah, vim has packages too… but they’re not as cool or easy to install as Emacs :)

The emacs community has made an insane amount of useful packages that are super easy to install. Here are a few:

4.2.1. MELPA

Essentially a repository of user-made extensions for Emacs. Think of this as the AUR.

4.2.2. SLIME

Get into a great Lisp interactive session!

4.2.3. Magit

Great for git interaction!

4.2.4. Company-mode

For completion

4.2.5. Undo-tree

For undoing your work in a neater fashion

4.2.6. LSP-mode

For running language servers

4.3. It’s written in Lisp

We’ve already taken a look at Elisp, but Lisp goes far more in depth than our simple breach of the surface. It’s by far my favorite language, and it has influenced language since its creation in the 60’s (10 years before C).

Lisp is wholly functional, which is great in comparison to ugly Object-Oriented languages like Java. (Really, OOP is fine where necessary but it gets really bloated really really fast)

5. First steps in going forward with Emacs

5.1. Want to learn ELisp?

I recommend reading “Writing GNU Emacs Extensions”. It goes into detail with Lisp, Emacs functions, and how everything works under the hood. It’s an O’Reilly book, so you get it free through USU.

5.2. Want to get started with Emacs?

Dive right into emacs by installing it with whatever package manager you use.

Read the guide that is accessible on the default emacs start page! It will teach you the basics of movement and usage of the software. From there, just search around the internet for resources. There are plenty.

If you need help or a recommendation, you can start at the emacs wiki. Or ask on the FSLC Discord in the `emacs-lisp` channel.

6. The compromise

6.1. Can’t decide which is better (it’s emacs)? Good news! You don’t have to!

Let’s take a look at the “evil-mode” package. This project aims to have 100% vim emulation within emacs. Whatever Vim can do, Evil Mode can do it too.

A great pre-built bundle for Emacs, called Doom Emacs, is great for new users who have familiarity with vim keybindings.

6.2. More on Doom

Personally, I used to use my own Emacs configuration that I wrote my own extensions in Lisp for, but Doom has much saner defaults so I switched. Default Emacs looks ugly as hell: